Taking the heat out

06-20-2014

House prices

Increases in interest rates will at best slow Britain’s housing boom

THE screws on Britain’s housing market are being gently tightened. New figures published on June 17th showed that in the past year house prices in Britain increased by 10%. In London they rose by almost 19%. Such increases look unsustainable; so Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, has said he will “not hesitate” to quell the market if necessary. He had already hinted that interest rates might go up sooner than expected—perhaps suggesting a rise this year.

House prices are soaring mostly thanks to government policy. Though the Bank’s base rate has been at just 0.5% for five years, mortgages remained relatively expensive and hard to get until late 2012, when a scheme called Funding for Lending was introduced to funnel public money to struggling banks. Since then, rates have fallen steadily and house-buyers have been borrowing more. Loan-to-income ratios for first-time buyers are at their highest recorded levels. In London, cash buyers have also played a big part in the boom. Some are foreigners, but most are probably well-off locals, using their savings to buy homes as investments or for their children.

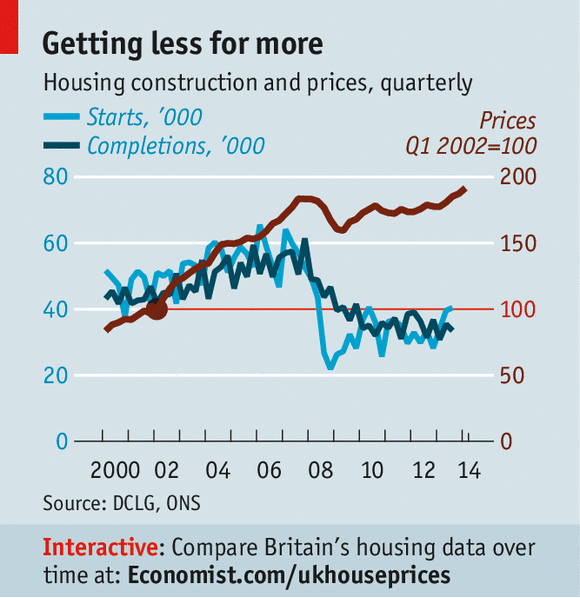

This surge of money into housing has combined with a chronic shortage of supply to boost prices. Population growth suggests as many as 250,000 new homes are needed in England alone to keep up with demand. Yet construction has undershot that for years: just 112,630 homes were completed in the year to April 2014, a third less than in 2007. The latest figures on housing starts (see chart) suggests things are improving, but not nearly enough. Building is unlikely to get much past its pre-recession highs before at least 2020, reckons Mark Clare, the boss of Britain’s biggest builder, Barratt Homes, and even then only with sustained government support such as help-to-buy, which subsidises mortgages for first-time buyers.

In other senses too, the recovery is tentative. Though first-time buyers are taking on more debt, there are not all that many of them: total mortgage lending is almost flat. In the year to April, 1.1m homes changed hands: a big increase on the recession-era low of 850,000, but still far below the 2007 peak of 1.7m. In most of the country—excluding London, the south-east and east—house prices remain below their peak. In some poorer northern towns, they are well below the level of a decade ago.

This leaves Mr Carney needing to pull off a difficult trick: to restrain house prices in the places where they are bubbliest without denting the broader economic recovery or causing a crash. Raising interest rates sharply would slow the housing market, but also hit firms borrowing to invest and consumer spending, which would damage the wider economy. But to do nothing might lead people to take on debts they cannot repay when rates eventually rise. To cool only the most overheated parts of the housing market, Mr Carney therefore appears to be preparing the ground for a combination of gentle rate rises with reforms to the mortgage market.

The merest hint of these measures may be having some effect. Even before Mr Carney’s speech, two big lenders, Lloyds and RBS (both of which are partly owned by the state) pledged to impose a loan-to-income cap on high-value mortgages. Since the speech, some of the cheapest mortgage deals have disappeared. And new rules introduced in April will stop some people getting big mortgages. Estate agents say this sort of gentle meddling ought to slow the precipitous price increases without strangling the property market’s recovery.

What monetary policy cannot do is fix the deeper problem—which is that houses will remain least affordable in the places where most jobs are being created. Price increases in the capital are making lots of money for construction firms who own land: Berkeley Homes, a London-focused builder, increased its profits by 40% in the year to April. But they are not stimulating much supply, largely because planning restrictions are so tight. In St Albans, a southern commuter town, the price of greenfield land with planning permission has already eclipsed its heady pre-recession levels. Yet where there is actually plenty of land with permission to build, for example in the Thames estuary, house prices remain too low to entice builders.

George Osborne, the chancellor of the exchequer, at least understands the problem. “British people want our homes to go up in value, but also remain affordable,” he said in a recent speech. Yet he has offered no new solution to London’s unaffordable housing. The green belt surrounding the capital, on which building is banned, will remain intact. House-building will therefore be limited to former industrial sites which are expensive to build on. As a senior civil servant notes, Britain’s housing market is getting back to its pre-recession normal state: broken.